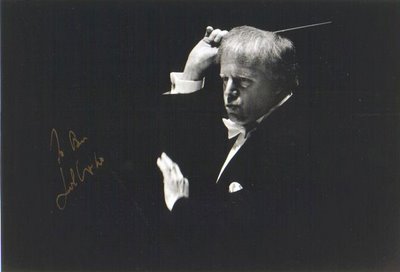

“The Chicago Symphony Orchestra family is very excited to celebrate both its newly formed relationship with Bernard Haitink and the continuation of its long standing relationship with Pierre Boulez,” said Deborah R. Card, President of the CSO Association. “Our strong commitment to maintaining the high quality of music making for which the CSO is known is further strengthened by the appointment of these two distinguished masters. We are thrilled that these gentlemen have agreed to collaborate with us as key members of the CSO’s artistic team.”

“As our music director search moves into its next phase, we are extremely pleased that Mr. Boulez and Mr. Haitink have accepted these new titled positions with the CSO. It is an honor to have musicians of such an extraordinary caliber working in these capacities,” said William H. Strong, Chairman of the CSO’s Board of Trustees and Chair of the CSO Music Director Search Committee. “Our search committee continues to find great inspiration in the knowledge that the best artists from around the world are so enthusiastic about working with our Orchestra. We remain energized in our music director search to select the best musical leader who is the right match for the CSO. We intend to take the time necessary to make a decision that will best serve our Orchestra and our city in the long term.”

“The Chicago Symphony Orchestra members who serve on the Music Director Search Committee are incredibly pleased with this announcement,” said CSO Assistant Principal Oboe Michael Henoch, on behalf of the musicians of the committee. “We hold Pierre Boulez in great esteem. For many years, he has conducted the CSO with the highest distinction as our Principal Guest Conductor. We are most grateful to him for the loyalty and dedication he has shown the Orchestra in agreeing to fulfill many administrative duties in coming seasons as well. Our admiration for Bernard Haitink has grown since he first conducted the Orchestra in 1976. He has always been a most welcomed guest conductor in ensuing years. Mr. Haitink’s latest residency this past winter confirmed that a very special relationship has developed between him and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. We look forward with great anticipation to our future music making with him.”

In his new role as Principal Conductor, Bernard Haitink will lead four to six weeks of CSO performances each season, starting in the 2007-2008 season, including subscription concerts at Symphony Center and tour performances. In addition to his Chicago appearances, Mr. Haitink will lead the Orchestra in future concerts at New York City’s Carnegie Hall, at the prestigious Lucerne Festival in Lucerne, Switzerland, and at London’s BBC Proms. His next scheduled dates with the CSO are in October 2006 when he will conduct the CSO, mezzo-soprano Michelle DeYoung, and the women of the Chicago Symphony Chorus in Mahler’s Symphony No. 3. He will also now return to Chicago in May 2007, leading the Orchestra in Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, Lutoslawski’s Chain 2 with CSO Concertmaster Robert Chen as soloist, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7. Mr. Haitink replaces Manfred Honeck for these performances.

Beginning in 2006-2007, as Conductor Emeritus of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Boulez will conduct three to four weeks of CSO performances each season, including touring activities. As previously announced, the CSO will perform three concerts under his direction at Carnegie Hall this December 2006. These will be complemented by future Carnegie dates. Mr. Boulez next returns to the CSO podium in late November/December 2006 for performances of Mahler’s Symphony No. 7, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin, Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales, and Ligeti’s Piano Concerto with soloist Pierre-Laurent Aimard.

“The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a truly great orchestra, with an extraordinary legacy and tradition. I am very proud to be a small part of that tradition, and I’m really looking forward to making music with these wonderful musicians,” said Bernard Haitink. Mr. Haitink made his debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in March 1976. He returned to Chicago over 20 years later to conduct subscription performances in January 1997. Most recently, Mr. Haitink led the CSO in a highly-successful two-week Chicago residency in March 2006.

“I am not only pleased, but deeply touched about being named Conductor Emeritus of the CSO,” said Mr. Boulez. “My gratitude and joy go far beyond the title itself because it means a lot to me to continue a fruitful collaboration with these wonderful musicians, and a team and organization of the first magnitude.” The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s close relationship with Pierre Boulez began with his CSO conducting debut in 1969. Mr. Boulez returned to the Orchestra Hall podium in 1987, and began annual residencies with the CSO in 1991. He was named Principal Guest Conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1995. Since that time, his annual Chicago residencies have been much-anticipated events, exploring landmark works of the 20th century, providing fresh perspectives on established symphonic repertoire, and offering notable premieres of new works. The CSO/Boulez partnership has yielded dozens of commercial recordings, eight of which have been awarded Grammy® Awards.

Mr. Haitink and Mr. Boulez will provide input as to the overall artistic growth of the CSO. Mr. Haitink will lend his expertise and ideas on artistic matters. Beginning in 2006-2007, Mr. Boulez will assume additional behind-the-scenes responsibilities, working with the musicians of the Orchestra and management team, participating in auditions for open positions, and assisting with personnel issues as they arise.

Looking ahead, music making with Bernard Haitink and Pierre Boulez will serve as the foundation for exciting future CSO seasons. Further reflecting efforts to build strong, continuing relationships with great artists, an outstanding roster of internationally acclaimed guest conductors will join the CSO in 2007-2008, including but not limited to (in alphabetical order): Semyon Bychkov, Myung-Whun Chung, Christoph von Dohnányi, Charles Dutoit, Mark Elder, John Elliot Gardiner, Valery Gergiev, Alan Gilbert, Miguel Harth-Bedoya, Riccardo Muti, Kent Nagano, Antonio Pappano, David Robertson, Mstislav Rostropovich, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and Michael Tilson Thomas. In addition to tours with Mr. Boulez and Mr. Haitink, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra will embark on a two-week European tour under the direction of Riccardo Muti in fall 2007. Full details for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s 2007-2008 season, including artists, concert programs, and tour itineraries will be announced in February 2007.